Gruppeudstilling / Group Show

Biotechnosphere

28.08.2019–14.11.2019

Vernissage:

28.08.2019,15:00–19:00

Biotechnosphere er første gruppeudstilling på Tranen i seks år. De udvalgte kunstneres værker præsenterer en bred strømning inden for samtidskunsten. Stadig flere kunstnere bearbejder og afbilder teknologi som et levende væsen – og levende væsner som teknologi. Den natur, som mennesket udspringer af, er stadig sværere at skelne fra den kultur, som mennesket skaber. Et nyt landskab tegner sig, der er i så hastig forandring, at det ikke kan fanges i øjebliksbilleder. I stedet præsenteres en række værker, der vidner om en stor transformation. Værkerne vidner om noget af det, der er ved at gå til grunde, det, der er ved at vokse frem og det, der er ved at antage helt nye former. Teknologi er ikke blot en masse mekaniske genstande. Biologi er ikke blot dyr og planter. Begge dele må i lige så høj grad forstås som sfærer, der i dag indhyller kloden og er sværere og sværere at skelne fra hinanden.

Biosfæren er livets sfære. Den finder sin oprindelse i mikroskopiske encellede organismer. Over 3,8 mia. år har livet på jorden udviklet sig til komplekse økosystemer af planter, dyr, svampe, bakterier og andre livsformer. Men i løbet af især det 20. århundrede har biosfæren ændret sig drastisk. En ny sfære, den såkaldte teknosfære, er nemlig vokset frem med uhørt høj hastighed. Teknosfæren er ifølge geolog og ingeniør Peter Haffs nu udbredte definition alt, hvad mennesket har frembragt fra redskaber og maskiner over hele byer og infrastrukturer til landbrug, skovdrift og affald. Visse videnskabsmænd kalder den en ”parasit på biosfæren”; en gæst, som man frygter vil tage livet af sin vært og dermed også sig selv. Teknosfæren vurderes idag at være både meget tungere og mere divers end biosfæren. Beregninger opgør teknosfæren til at veje omkring 30 trillioner ton. Andre beregninger estimerer, at antallet af teknologiske frembringelser er mange gange større end biosfærens diversitet, der menes at tælle bl.a. 8,7 mio. dyre-, plante- og svampearter.

I 1926, da biogeokemiens grundlægger Vladimir Vernadsky publicerede den første storstilede teori om biosfæren, var dette sfæren, som han mente adskilte jorden fra alle andre kendte planeter. I dag under 100 år senere har teknosfæren vokset sig måske endnu større. Dens lys ses nu fra rummet takket være satellitterne, der samtidig markerer teknosfærens fortsatte ekspansion. Men teknosfæren er ikke en sfære for sig. Den er uadskilleligt viklet ind i biosfæren. Mennesker og domesticerede dyr tegner sig i dag for 97 procent af den samlede vægt af alle dyr på jorden. Det vil sige, der blot er 3 procent vilde dyr tilbage. I Danmark, der er det mest opdyrkede land i verden sammen med Bangladesh, dækker landbrug 57 % af landjorden.

Visse stemmer så som biologen Edward O. Wilson mener, at biosfæren må afkobles teknosfæren: ”Jeg er overbevist om, at vi kun kan redde den levende del af vores miljø og opnå den stabilisering, som vores overlevelse afhænger af, ved at forvandle halvdelen af jorden til reservat.” Andre så som MIT entreprenøren Caleb Harper taler omvendt for en ny og anderledes sammensmeltning af biologi og teknologi. Han arbejder på at udvikle såkaldte Personal Food Computers. Via et netværk udveksler brugere informationer om de grøntsager, som de gror i lukkede biosfærer i deres computere, der muliggør, at alle CO2 neutralt selv kan producere og forbruge den mad, som de spiser.

Kunstnerne i Biotechnosphere præsenterer hverken løsninger eller handlingsplaner. Deres værker giver snarere form til forestillinger om biologiske og teknologiske processer, der besmitter hinanden og kaster noget helt tredje af sig.

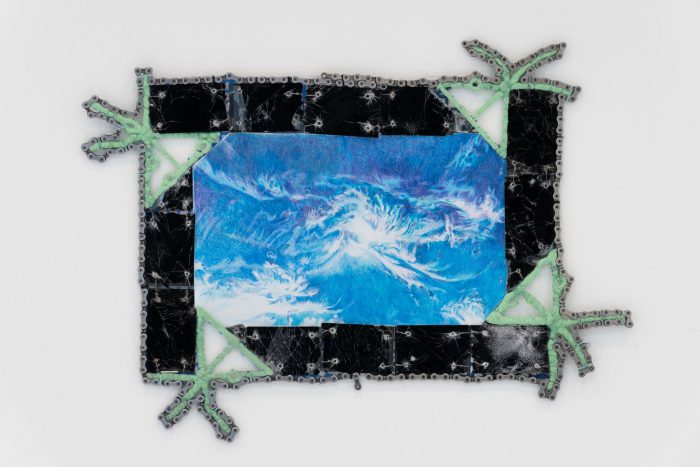

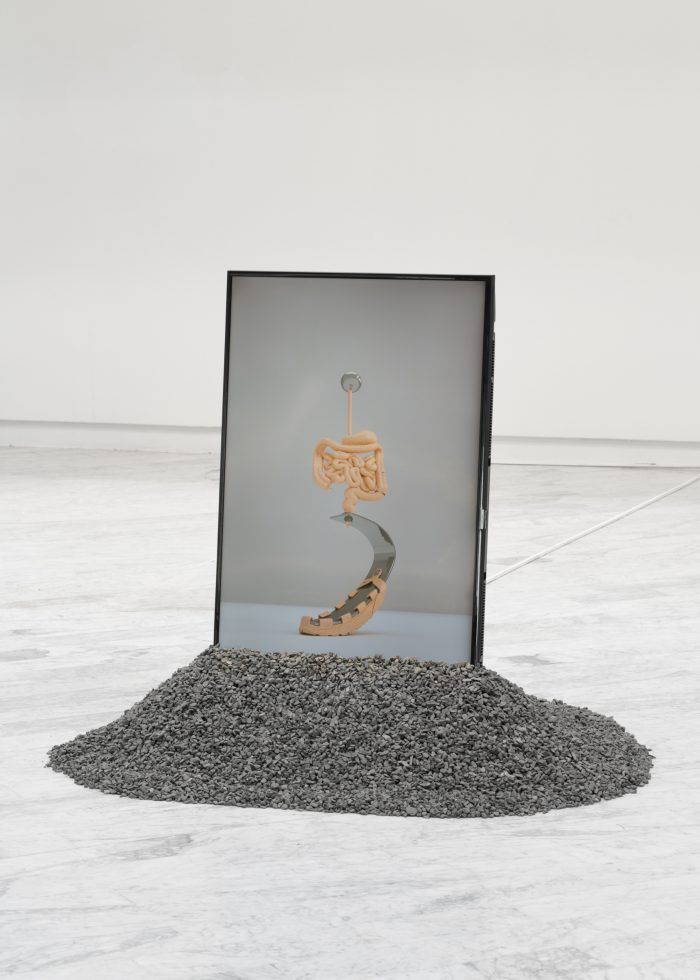

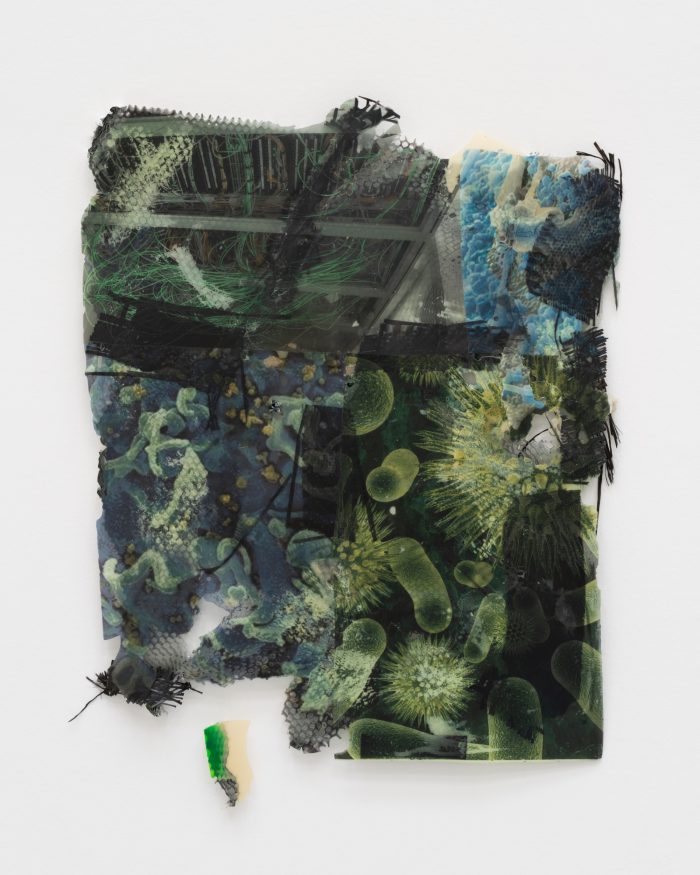

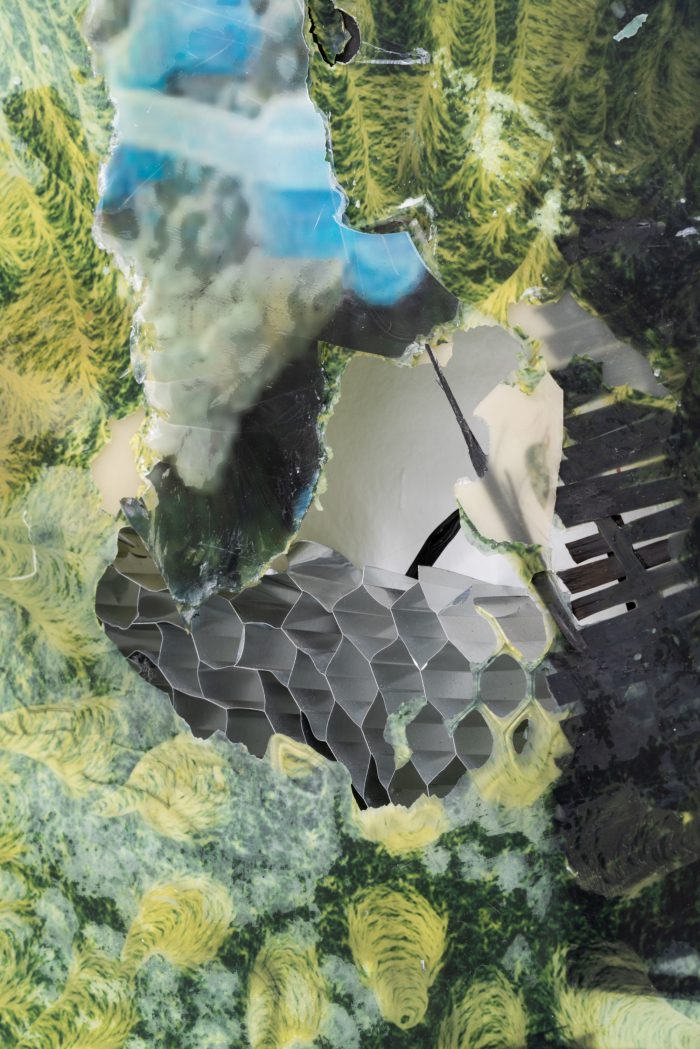

I franskmanden Anna Solals værker på gulvet synes fugle at rejse sig i sporene efter en stor kaffekop. I hendes tegninger på væggen er himlens smukke, livgivende atmosfære indrammet af ituslåede smartphone skærme og cykelkæder. Også i værkerne af Estrid Lutz fra Bosnien-Hercegovina fremstilles menneskets efterladenskaber på jorden som grobund for fremvækst. I hendes vægværker sammenvæves materialer fra bil-, satellit- og kommunikationsindustrierne med billeder af mikroskopisk liv, slangeskind og øgler. Lag af selvlysende maling giver indtryk af en totalt smadret verden svanger med liv og ånd. I danske Stine Dejas animationsvideoer på gulvet troner væsner af lige dele biologiske organer og teknologiske proteser, og i danske Emilie Alstrups tryk på akrylglas vrider sig en hybrid skabning, hvis enkelte dele man knap kan identificere. I deres værker møder man ikke bare et menneske i forvandling; et væsen, der teknologisk søger at tilpasse sig en verden i hastig forandring; det er som om, man også begynder at tabe mennesket af syne. I canadieren Jon Rafmans 8 min. lange video befinder vi os i en menneskeskabt verden, hvor der tilsyneladende ikke længere er nogen mennesker, blot vores teknologiske infrastruktur. En stemme taler, bl.a. om, at den ikke længere ved, hvorfor den taler. Det lyder som en digital stemme, måske en kunstig intelligens’. Måske filmen iscenesætter forestillingen om den såkaldte singularitet; det punkt i fremtiden, hvor kunstig intelligens vil overgå menneskelig intelligens; et punkt hinsides hvilket vor begrænsede intelligens ikke kan begribe, hvad vil ske.

Vi kan regne på bio- og teknosfærens udvikling. Men vi vil ikke kunne regne ud, hvad der vil ske. Det er sådan uvished, der nærer de kunstneriske forestillinger præsenteret på Biotechnosphere.

Udstillingen ledsages af litteratur udvalgt af Toke Lykkeberg.

Toke Lykkeberg

Leder af Tranen

Biotechnosphere er femte udstilling i Tranens program med ekstemporær kunst. Fokus er på den del af samtidskunsten, som ikke er fokuseret på samtiden. Når alt fra økosystemer til teknologi udvikler sig med stadig højere hastighed, bliver samtiden flygtig og uhåndgribelig. Den skrumper. Til gengæld vokser vor viden om fortiden konstant. Spekulationer om fremtiden tager til. Som del af denne bevægelse er megen samtidskunst ikke længere kontemporær, hvilket bogstaveligt talt vil sige ’med tiden.’ I stedet er den ’ekstemporær’, altså ’ude af tiden.’

Udstillingen er støttet af Det Obelske Familiefond og Statens Kunstfond.

Biotechnosphere is the first group show at Tranen in six years. The works of the selected artists present a major current in contemporary art. More and more artists address technology as if it were living matter – and living matter as if it were technology. Nature from which mankind originates is still more difficult to tell from the culture that mankind creates. A new landscape surfaces, one that’s changing so rapidly it’s close to impossible to capture in its moment. Instead, a range of works is presented that bear witness to a great transformation. The works bear witness to what is about to perish, what is about to emerge and what is about to take on entirely new forms. Technology is no longer merely mechanical objects. Biology not merely animals and plants. Both are equally to be thought of as spheres, which envelop the globe and increasingly seem indistinguishable from one another.

The biosphere is the sphere of life. It finds its origins in microscopic single-celled organisms. For over 3,8 billion years, life on earth has evolved into complex ecosystems of plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other lifeforms. But especially during the 20th century, the biosphere has been subject to dramatic change. A new sphere, the so-called technosphere, has grown forth at unheard of speed. The technosphere is – according to geologist and engineer Peter Haff’s now widespread definition – everything that humans have created from tools and machines to cities and infrastructures to agriculture, forestry, and waste. Certain scientists call it a “parasite on the biosphere”; a guest, which one fears will take the life of its host and, as a consequence, also itself. The technosphere is today estimated to be both much more heavy and diverse than the biosphere. Calculations assess the technosphere to weigh around 30 trillion tons. Other estimates suggest that the number of technological devices is much higher than the diversity of the biosphere, which according to one study accounts for about 8.7 million animal, plant and fungus species.

In 1926, when the founder of biogeochemistry, Vladimir Vernadsky, published the first comprehensive theory of the biosphere, this was the sphere he thought set earth apart from all other, known planets. Today, less than 100 years later, the technosphere has arguably grown even bigger. Its light is now seen from space thanks to satellites, which also mark its ongoing expansion. But the technosphere is not a sphere apart. It is inextricably entangled in the biosphere. Humans and domesticated animals today constitute 97 percent of the total mass of all animals on earth. Hence, there is only 3 percent wild animals left. In Denmark, which is the most cultivated country in the world alongside Bangladesh, agriculture covers 57 % of the land.

Certain voices such as biologist Edward O. Wilson argues that the biosphere must be disconnected from the technosphere: “I am convinced that only by setting aside half the planet in reserve, or more, can we save the living part of the environment and achieve the stabilization required for our own survival.” Others instead push for a new and different kind of fusion of biology and technology. One is MIT entrepreneur Caleb Harper, who is currently working on developing so-called Personal Food Computers. Through a network of interconnected users, who exchange data about vegetables they grow in enclosed biospheres in computers, he envisions a CO2 neutral world, where everyone produces and consumes the food they eat.

The artists in Biotechnosphere present neither solutions nor plans of action. Rather, their works give shape to visions of biological and technological processes that clash and coalesce. In French artist Anna Solal’s floor works, birds seem to rise from stains from a big coffee cup. In her drawings, a beautiful stretch of life-giving blue sky is enclosed by smashed smartphone screens and bicycle chains. In a similar vein, in the works by Estrid Lutz from Bosnia-Hercegovina, earth is a dump that serves as a breeding ground for new composite lifeforms. In her wall works, materials from the automotive, satellite and communication industries converge and merge with imagery of microscopic life, snakeskin, and lizards. Layers of glow-in-the-dark paint ooze of a bygone world re-animated by life and spirit. In Danish artist Stine Deja’s animations on the floor creatures part biological organs, part technological prosthesis stand tall, while in another Danish artist, Emilie Alstrup’s prints on acrylic glass, a hybrid being twists and turns to the point where its constituent parts start to blur. In these works we do not just confront human beings in transformation; beings that technologically adapt to a rapidly changing world. It’s as if one is also about to lose sight of mankind. In Canadian artist Jon Rafman’s 8 min long video, we find ourselves in man-made world, where there aren’t any humans left, apparently, only technological infrastructures. A voice speaks, among others about not knowing why it’s speaking. It sounds like a digital voice, perhaps that of an artificial intelligence. Perhaps the film stages the scenario of the so-called singularity; the point in the future, when artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence; a point beyond which our limited intelligence cannot comprehend what will happen.

We can compute the state and development of the bio- and technosphere. But we cannot figure out what will happen. It is among other things such uncertainty that nourishes the artistic expressions on display in Biotechnosphere.

The exhibition is accompanied by a selection of fiction and non-fiction books curated by Toke Lykkeberg.

Toke Lykkeberg

Director of Tranen

Biotechnosphere is the fifth exhibition in Tranen’s program about extemporary art. The focus is on contemporary art that is not primarily focused on our contemporary condition. When everything from climate to technology evolves at ever greater pace, the present becomes ephemeral and intangible. The present starts to shrink. Meanwhile, our knowledge of the past increases. Speculations about the future abound. As part of this development, much art is no longer contemporary, which literally means ‘with time.’ Instead, art is rather ‘extemporary, i.e. ‘out of time’.

The exhibition is generously supported by Det Obelske Familiefond and The Danish Arts Council.

Anbefalet læsning / Recommended reading:

Forfatter / Author

Titel / Title

Udgivelsesår / Publication date

Samuel Butler

Erewhon: or, Over the Range

1872

Christophe Bonneuil & Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us

2016

Rachel Carson

Silent Spring

1962

Buckminster Fuller

Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth,

1968

Donna Haraway

When Species Meet

2008

Kevin Kelly

Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World

1994

Ray Kurzweil

The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology

2005

James Lovelock

A Rough Ride to the Future

2014

Edward O. Wilson

Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life

2016

Susan Hockfield

The Age of Living Machines, How Biology Will Build the Next Technology Revolution

2019

Martin Heidegger

The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays

1977

Vladimir Vernadsky

The Biosphere

1926

Norbert Wiener

The Human Use of Human Beings

1950